Best Book: Shirley Jackson, We Have Always Live in the Castle

Best Book: Shirley Jackson, We Have Always Live in the CastleDespite being up against some pretty stiff competition - even in the same week - and a last minute contender of The King in Yellow giving it a run for the finish line, the prize has to go to this neglected classic of murder and neurosis, of the sly ambiguous Merricat and her terrible days.

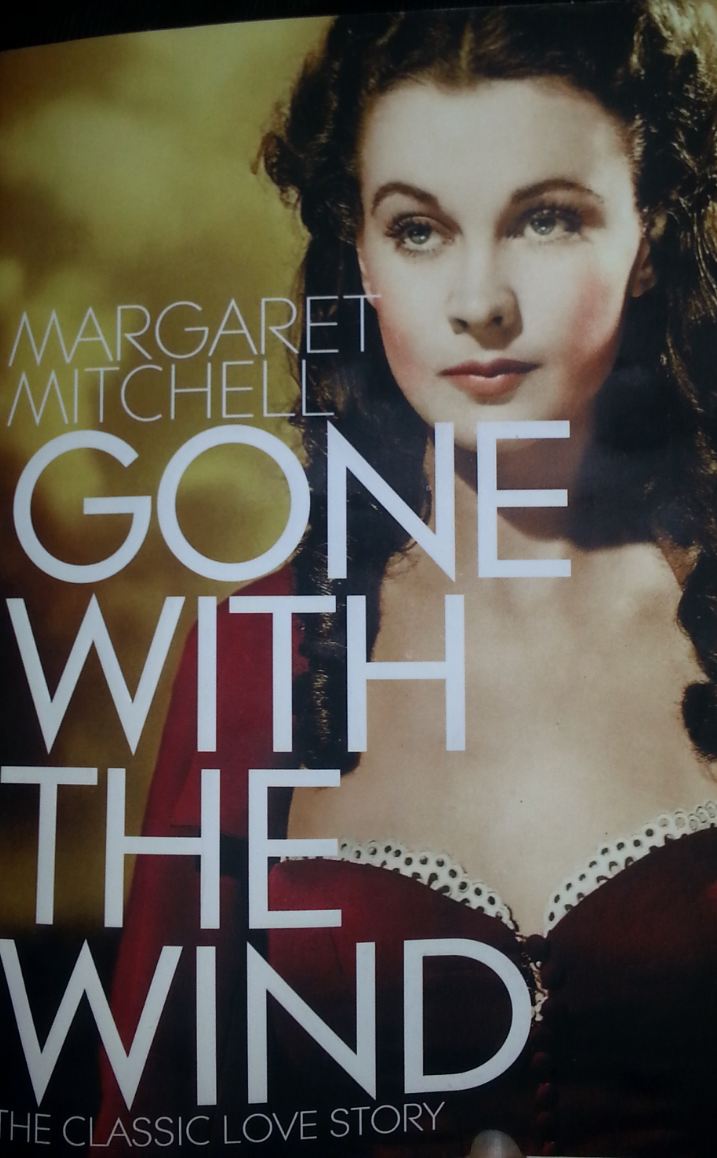

Worst Book: Margaret Mitchell, Gone With the Wind

This also had some competition from Dan Simmons' horrifically racist, Song of...

No. Wait. There was no competition. Simmons' orientalism is left staggering on the track asking, "Was it a bird? Was it a plane? No! It was a horrifically misogynist novel that makes light of two acts of genocide?"

Best Re-Read: Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years Of Solitude

This prize does not go to a re-read of the, "I'm ill, sod life, I'm climbing into a bath with Howl's Moving Castle" stripe, but rather the, "Jesus, has it been over ten years since I read that? Philistine." kind. One Hundred Years of Solitude is basically the blue-print for that regret. Since he passed away in April this year, I realised how much I had been neglecting his work and felt appropriately awful. Gloriously written, heartbreaking and archetypal, it is one of the most important books for the twentieth century. The sole advantage of leaving it far too long was that it was fresh to me again. Worth every moment of the hype you have read everywhere else. I didn't blog it because I didn't really feel my voice had anything to add. If you haven't yet, put it on your list for next year.

The New Release of JOY! Prize: Paul Cornell, The Severed Streets

Aka, the Justified Fangirling Award. Utterly brilliant magical-police-proceedural/ horror novel from the alway wonderful Mr Paul Cornell. Don't read it quite as fast as I did (or, if you do, reread it afterwards), and check out London Falling first.

The "Neil Who?" award for Writers Who I Now Like: Nick Harkaway, Angelmaker

Remember that moment before you had heard of your favourite writer? When their name meant nothing to you except that it was printed on the jacket of a book you were about to start reading? Remember that feeling when you suddenly realised that this wasn't the only thing they had writen? Or that they had a new book coming out in six months?

Well, the "Neil Who?" is given to writers who capture something of that feeling. It has a few rules - they must still be alive, and the book must be relatively recent (last ten years.)

So, whilst honourable mention must go to Max Barry's superlative Lexicon, it is Nick Harkaway's back catalogue after which I shall be chasing in the new year.

And finally....

The Captain Bluebear Award for Appreciable Weirdness goes to Walter Moens for The Thirteen and a Half Lives of Captain Bluebear. If I get a chance to reaward this prize next year, I shall be a very happy pink bear of medium size.

Many thanks to all the wonderful writers who are out there creating fabulous stuff either in the past of present for not volunteering to take part in the Alys Earl Book Awards 2014. To all the non-writers out there: Read more books.

Happy New Year.