|

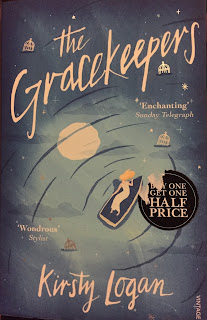

| This month's book-club book! |

When you call a woman (and with a divorce, a round of failed IVF and a drink problem, there is no 'girl' about Rachel) a girl, you are presenting the kind of attitude towards women and their problems that wrecked Gone Girl for me. I was expecting another round of 'psycho ex-girlfriends' and false rape accusations - which is, I admit, generally better than the tough-but-vulnerable manic pixieness you get when men use such titles.

I wanted SO BAD not to like this book.

But I'm sorry to tell you that it's brilliant.

No, it's not the best book I've read this year, but it is a gripping, sickening and intelligent thriller. The characters are complex, realistic and never entirely likeable. Their problems are real, and - even if you hate them - you will pity them. Their suffering wrenches through the novel with a powerful 'here but for the grace of god'. It's the stuff of nightmare, but the worst nightmares, the kind that bubble so close to the surface of our experience of the world. It presents, terrifyingly, the real stakes of living as a woman in the patriarchy, and the way that you will often find yourself at the mercy of men, with no guarantee of their good intentions.

I struggled, I admit, at points with some of the set-up (spoilers, sorry) - the plot relying on a couple of tropes we could do without for the next eight decades - and found the ending possibly a little sensationalist. The mystery aspect itself was competent and well structured. I admit, I sussed it a little before time, but only due to certain personal reasons - my suspicions did not cement until the proper moment, when the careful laying of clues coalesced into certainty. One aspect of this was especially well presented, and actually did catch me by surprise.

The real draw of The Girl on the Train, however, is not its mystery, but the claustrophobic, almost unhealthy intensity of emotion within it, and on that count it hits every single mark. Fantastic, and well worth your time.