The vampire is prone to be fascinated with an engrossing vehemence, resembling the passion of love, by particular persons. It will never desist until it has satiated its passion.... In these cases it seems to yearn for something like sympathy and consent. -Sheridan Le Fanu, Carmilla

"Resembling?"

I remember reading it the first time. I put down the book, stared up, frowning at the ceiling (light green, artex. My adolescent bedroom), rubbing the tattered paper of the spine.

"Resembling?"

After all, I was a Buffy fan, had seen enough of Angel's brooding, heard Spike's immortal line:

I wasn't surprised to find the idea of vampiric obsession, the idea that vampires were capable of strong, even affectionate, emotion towards humans and each other - what bothered me was the line being drawn. "Resembling."

The affection Carmilla has for the narrator is evident, her passion clear - why, then, the reluctance to call it by it's name?

Dracula, too, is charged with an inability to love, and answers, "Yes, I too can love. You yourselves can tell it from the past." What's more, the person accusing him is one his 'wives' - another vampire, suggesting that love is valued by the Undead, that Dracula's lack of it is an aberration. However, context is important; the 'love' to which the wives are refering involves eating the object of their desire. What's more, Dracula counters their criticism by claiming that he had once loved them in the same fashion - three women whom he seems to ignore when he isn't indulging them with a baby-in-a-bag, women he is in the process of abandoning.

The Dracula we see in the novel is alone, almost tragically so.

Vampiric love, then, is one which it is difficult to seperate from appetite, from death. After all, Carmilla talks of love and passion without reservation, but it is clear she means something a lot less sanitary than chocolate boxes and billet doux. She recalls "a cruel love - strange love, that would have taken my life," believes, "Love will have its sacrifices." Even in Buffy (which was my teen-relationship textbook) vampire romance is never healthy - there's Angel's painful impossible love of Buffy; there's Spike and his glorious, dysfunctional infatuation with Dru; and there's Dru swooning over Angelus, the monster who drove her insane.

Perhaps that's what Le Fanu was getting at - we can recognise the strength of the feeling, its passion, its realness - but ultimately it either fickle, self-serving, or destructive. It is not a wholesome, it offers no support or strength, can only kill one or both parties. Although similar to love in many ways, it cannot be love because, by definition, its focus, its practicioners are perverse.

Transgression, Perversity and Otherness:

Hmmm. Yes.

Hopefully it is news to no-one that vampires are often used as a sexual metaphor. However, the sex they represent is seldom normative, sanctioned sexuality - monogamous, heterosexual, vanilla, and focused on reproduction. Vampires are used to explore Otherness, and one way to do that is to present them as sexually 'transgressive'. This holds true, even at a surface reading: Carmilla is a lesbian, Spike a male submissive, Dracula a bigamous foreigner. If I started to list the gay vampires out there, we would be here all day.

And one of the ways that Othering dehumanises a figure is to present their emotions and reactions as deviant, immature, perverse. Because they are different to us, because they are 'less' than us, their emotions and motivations can never be as real, important, or respectable as the feelings of mainstream groups.

So just an Other cannot be forthright, but rather is shrill or beligerant, what they believe to be love is not really love. It is merely lust, infatuation, obessession. Their relationships are perversions and inverstions of the ones that 'we' practice, the 'real' relationships. When they run against us, their attentions are clinging, embarrasing, unwelcome. Their influence is corrupting by default.

Yes, this fits the metaphor of vampirism rather nicely, doesn't it?

And metaphors are powerful. If these stories show, over and again, that the only 'right' love is male-dominated, heterosexual monogamy, then anything which falls outside of that, which is represented by vampires, is dangerous, evil, corrupt.

And, like many things didactic moralists preach against, it also looks kinda fun.

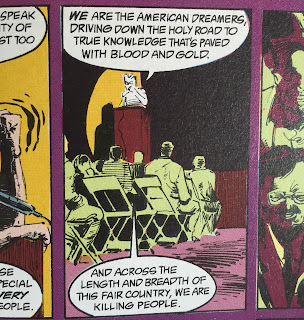

Take me away from all this death.

"Make me into one too," said the boy. "Please? I want to be one. I want to walk the night with you and fall in love and drink blood. Kill me. Make me into a vampire too. Bite me. Take me with you." - Poppy Z. Brite, Lost SoulsOh, who hasn't at least thought about it? About being eternally beautiful, unbreakable, strong?

Sympathy for the vampire is not an uncommon reading, or indeed response to the genre, and the reaction against such sympathy it is always strong, morally guided and didactic.It's well known that the British Board of Film Classification pushed for censorship of Hammer's vampire films because of the sexual element of the biting scenes, especially Mina's almost gleeful acceptance of Dracula's advances.

Even today, there are no shortage of people who seem to want to drag vampirism back into the realms of 'good, clean horror'. But these currents have always been there. The real power of vampirism is neither in its desirability, nor its horror, but in the ambivalence it raises. As the narrator of Carmilla says:

In these mysterious moods, I did not like her. I experienced a strange tumultous excitement that was pleasurable, ever and anon, mingled with a vague sense of fear and disgust. I had no distinct thoughts about her... but I was conscious of a love growing into adoration, and also of abhorrance. - CarmillaWe are aware of the moral failings of vampires, even as we are drawn to them. They may be tragic and lovely, but they cannot be saved.

Something in him ached for that boy. For the sadness in his face, for his eyes yearning to stay young. He wanted to grab Nothing away from his companions and tell him that sometimes, everything could be all right, that pain did not have to come with magic, that childhood never had to end. And yet he wondered whether Nothing had not known all those things when he made his choice. - Lost SoulsWriters do fascinating gymnastics to navigate this problem, but ultimately, it will always be as Carmilla says, "I live in you; and you would die for me, I love you so." It is a mad love, is amour fou - another thing which is belittled, mocked, denegrated. It is another thing that is often described as not 'really' being love, only 'resembling' it.

But, oh, it is so very real, and so very tempting. It is a love which transgressive, morally ambivalent, one that can bring with it an entire world of pain. And many vampire writers chase so hard after it, trying to bring it to a happy ending. But tidying away its danger, its nastiness, its utter disregard of morality, it is very difficult to maintain its white-hot intensity. If a vampire is prepared to call your father, 'sir' and wait until marriage, passion can hardly be consuming him that badly, right?

Well, maybe. There is such a thing as self-control. And, after all, Le Fanu speaks of an "artful courtship" of longing for "something like sympathy and consent"?

|

| Take me away from all this death! |

That "like" again.

The Boundaries of Metaphor, the Limits of Consent:

As mentioned above, the sympathy is easy. It's the heart of the vampire's allure, after all. It is precisely that balance of attraction and disgust. The idea that something about you is being admitted that you would never have owned before. It is about a sense of transgression, of non-normativity. It's about self discovery - and the ensuing shame, ambivalence, emergence.

The reinvention of the vampire as a romantic hero comes from that longing, that desire to put away all the weakness and uncertainty, to have your secret desires unfolded, to be lifted up on a love that is actually forever. So, of course it appeals, it is so tempting to leave it at that.

But consent? Oh, how on earth do do we negotiate the morality of this?

After all, this is not coming out or getting laid. It's not asking your partner to spank you: we are talking about a vampire. This is someone who kills humans in order to live. So, yeah, you might sympathise, but that won't stop you reaching for the stakes and the communian wafer.

Besides, even if it didn't, can a word like consent actually be used in these circusmtances? The watchword of the BDSM community is SSC - safe, sane and consensual - and if consent is the most discussed, it does not exist in isolation. The three are interdependent - without consent and safety, it cannot be sane; without consent and sanity, it is not safe; without safety and sanity you cannot be said to have consented.

Also, legally, certain things are out of bounds, no matter how much you might want someone to do them to you. Being eaten, for example.

How can vampire romance ever be unproblematic?

So people tidy things up. They removed the Otherness of vampires, stop them being killers, make them just humans with better hair and super-strength. But this overlooks the power of that Otherness, the importance of vampire mythos to groups who have been Othered, told their desires are dirty, immoral, or just worthy of mockery.

Contemporary vampire novels are frequently queer, or kinky, or else the dream relationships of lonely women of various ages*. To love a vampire is to desire to turn outsider status in to the ultimate in-group, to rewrite loneliness and frustration in to endless pleasure, to cast off low self-esteem nd find body confidence, beauty and sexual agency.

So we write stories where there are 'good' vampires, where they have souls and don't eat humans, and it becomes all about the metaphor. These are good people, just like us, facing unfair discrimination. The fact they must live in secrecy is unjust. The huge taboo surrounding vampire love is misguided.

However, as an idea of 'devaint love reclaimed as permissible', vampirism is a flawed model. To be able to embrace it wholeheartedly involves tidying away the ugliness, the whole vampire bit of vampirism. Female sexual agency isn't actually fatal, and lesbianism is does not cause aneamia. There is a lacuna between the metaphorical truth of vampirism-as-sexuality and its narrative reality. A young queer person may be justified in feeling that coming out will get them treated like a monster - it happens far too often - but they will never become one. Kinky sex (or, honestly, just sex) may feel dangerous, furtive and transgressive - but it should never actually be so.

Vampirism is. Its whole draw is the idea of being wanted so badly by someone that they will devour you. But this isn't a brutal slash and hack job - it is tender, loving, slow. It is romantic, sensuous, arousing.

And it will kill you.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Mine is, arguably, all three.